Washington Post Obituary by Emily Langer

Bogaletch Gebre nearly bled to death around age 12 when, like almost all Ethiopian girls of her generation and before, she was subjected to the excruciating ritual now known as female genital mutilation.

A man restrained her while two women held her legs and a third wielded the razor. Her mother cried as Ms. Gebre was led away for the cutting ceremony. She would have liked to spare Boge, as Ms. Gebre was known, but saw no way to avoid the ordeal.

“Cleansing the dirt,” the local term for genital cutting, was treated across faiths in Ethiopia as a religious rite that rendered a young woman marriageable. Many victims died from blood loss, infection or subsequent complications.

Ms. Gebre, who had already defied expectations for Ethiopian girls in her village by secretly learning to read, went on to devote her life to ending female genital mutilation, as well as bridal abduction, domestic violence and other scourges that combined, she said, to make Ethiopian women “live in fear every day of their lives.”

She led change not with demonstrations or confrontation, but through what she described as community conversations facilitated by a nonprofit organization she co-founded and involving women as well as men.

FGM, while declining, continues to be performed in Ethiopia, as in other African countries, the Middle East and Asia, where the tradition is most prevalent, according to the World Health Organization.

But in the areas of Ethiopia where Ms. Gebre worked, the improvement has been marked: Only 3 percent of villagers in 2008, down from 97 percent in a survey eight years earlier, said they wished for their daughters to undergo FGM, according to figures cited in a 2010 UNICEF study.

Ms. Gebre, described by the London Independent as “the woman who began the rebellion of Ethiopian women,” died Nov. 2 in Los Angeles, according to an announcement by KMG Ethiopia, the organization she co-founded in 1997 with her sister. The cause was not provided. Ms. Gebre was unsure of her age, having never received a birth certificate, but was thought to be 65 or 66.

She had lived in Los Angeles during and after graduate school and returned periodically to the city to receive treatment for nerve damage she sustained in a car accident in 1987, according to an obituary published in the Los Angeles Times.

Ms. Gebre’s life took her from a farming village in central Ethiopia where she stole away for schooling during long trips to collect water, to scientific studies at universities in Israel and the United States, and back to Ethiopia, where she won the respect of women as well as men, who, it was said, were astonished to see a woman achieve such success.

She was born in 1953, according to her nonprofit organization, in Zato, a village in the Kembatta district, southwest of the capital of Addis Ababa. Most of her 13 siblings died in childhood.

Ms. Gebre described her mother as intelligent and wise but told the Independent she and other women were “regarded as no better than the cows they milked.”

“All her life she was abused and beaten — for nothing,” Ms. Gebre said. “She had her back stooped, her legs broken, her jaw broken, even though she did everything right. It was a nightmare, but for her it was a life. And somehow she still smiled. When there is no alternative, you somehow accept this as all you will get. In that situation, many women accept their situation as God-given, not man-made.”

Ms. Gebre was said to have been the first girl in her village to receive schooling beyond the fourth grade. With her hard won literacy, she helped fellow villagers read official documents they otherwise would not have been able to decipher.

“As a sign of respect in Kembatta tradition, a father is called after his firstborn son, and a mother after her firstborn daughter,” Ms. Gebre recounted years later to the Ethiopian-American publication Tadias. “Imagine his surprise when my father’s peers started calling him ‘Father of Bogaletch.’ ”

She received a scholarship to enroll at a women’s boarding school in Addis Ababa, then studied the sciences at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. She received a master’s degree from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, according to KMG Ethiopia, and pursued further graduate studies in epidemiology at UCLA.

She traced her fervor for ending FGM to the death of a sister during childbirth to complications caused by FGM, which made it impossible for her to deliver her twins.

“From that moment I couldn’t stop thinking about it,” Ms. Gebre later told the publication Africa News. “My goal was: Can I save one girl from that horror? It became the drive for what I started.”

She left California for Ethiopia and founded her organization with another sister, Fikirte. The KMG of its name stands for Kembatti Mentti Gezzimma, which has been translated as “Kembatta Women Standing Together.”

Ms. Gebre won the cooperation of communities by first providing practical services, such as the construction of a bridge or well. Slowly, she began encouraging dialogue on such topics as education for girls, HIV/AIDS and the kidnapping of young women into marriage. During discussions of FGM, she showed videos of the procedure that left men physically ill.

“People in villages may be illiterate, but they are not stupid. They want what’s good for themselves and their children,” the medical journal the Lancet quoted Ms. Gebre as saying.

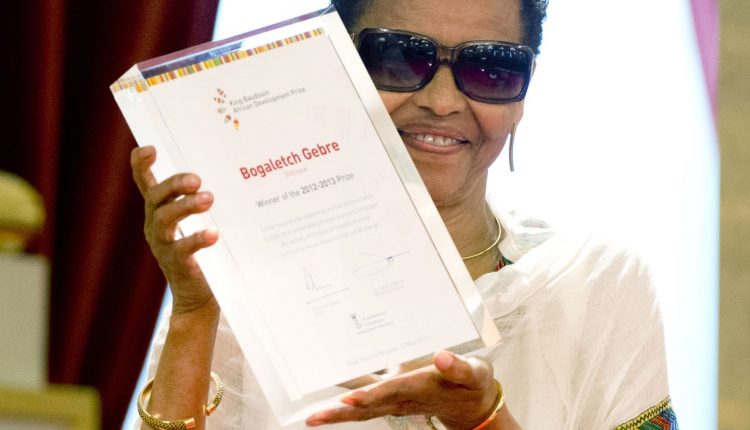

Over the years, her organization has worked to promote education and economic freedom for women, their participation in government and greater reproductive health. Ms. Gebre’s honors included the 2012-2013 King Baudouin African Development Prize, awarded by the Brussels-based King Baudouin Foundation.

“Not only have tens of thousands of girls and women been spared gross human rights violations, but the transformation of their communities goes far beyond that,” read the citation. “The status of women has changed so that not only do they now raise their voices, they are also heard and their communities have become more equitable overall.”

Ms. Gebre was never married and had no children. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

“I began KMG Ethiopia thinking that if I could save a single girl from a dreadful life, from practices that numb, crush the spirit and rob women of their dignity, I would have done my life’s mission,” she once said. She added that the “breakthroughs” — the first abducted bride returned to her family, the first uncut young woman married in a public celebration — come “one girl at a time, one person at a time.”